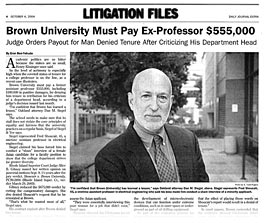

Judge orders payout for man denied tenure after criticizing his department head

Academic politics are so bitter because the stakes are so small, Henry Kissinger once said.

So the level of acrimony is especially high when the coveted status of tenure for a college professor is on the line, as a recent case illustrates.

Brown University must pay a former assistant professor $555,000, including $100,000 in punitive damages, for denying him tenure in retribution for his criticism of a department head, according to a judge’s decision issued last month.

“I’m confident that Brown has learned a lesson,” Oakland attorney Dan M. Siegel says.

The school needs to make sure that is staff does not violate the core principles of equality and fairness that the university practices on a regular basis, Siegel of Siegel & Yee says.

Siegel represented Fred Shoucair, 45, a onetime assistant professor in electrical engineering.

Siegel claimed his boss forced him to conduct a “sham” interview of a female Asian candidate for a faculty position to show that the college department strives for greater diversity.

Rhode Island Superior Court Judge Alice B. Gibney issued her written opinion on post-trial motions September 9, 1/2 years after the jury verdict. Shoucair v. Brown University, PC96-2896 (Rhode Island Super. Ct., verdict March 29, 2003).

Gibney reduced the $675,000 verdict by cutting the compensatory damages. She also denied Shoucair’s request that he be reinstated at Brown.

“That’s what he anted most of all,” Siegel says.

His contract expired after Brown denied him tenure.

The university’s trial counsel Christopher H. Little says Shoucair didn’t receive tenure because of the narrow scope of his research and inadequate grant funding.

The school has not decided yet whether to appeal, he says.

The engineering division already has agreed to offer a white male scientist the vacant post, Gibney’s decision states. But the school’s affirmative action committee raised questions as to why the department had declined to interview a number of promising Asian candidates.

To satisfy the committee, the secretary for Maurice Glicksman, the chair of the engineering division, asked Shoucair to assess the Asian applicant.

“They were essentially interviewing this poor woman for a job that didn’t exist,” Siegel says.

Shoucair objected, but Glicksman forced him to evaluate her anyway, Gibney wrote.

Glicksman allegedly punished Shoucair for his defiance by derailing his chances for tenure.

Little says that’s not ture.

“There never was any retaliation by Glicksman,” says Little, of Providence, Rhode Island’s Little, Bulman, Medeiros & Whitney.

During this time, Glicksman headed a three-member tenure review committee evaluating Shoucair. The committee recommended “without enthusiasm” that Shoucair receive tenure.

Shoucair worked at Brown from 1987 until 1994. His field of scholarship involved the development of micro-electronic devices that can function under extreme conditions, such as in outer space or underground as part of oil drilling equipment.

As part of the evaluation process for tenure, Shoucair nominated five experts to review his research. Each recommended that he receive tenure, according to court documents.

Gibney affirmed the jury conclusion that Glicksman’s conduct justified awarding $100,000 in punitive damages.

“Shoucair testified that Glicksman told him that his reference letters were positive and that there was no way Brown could deny him enture,” Gibney wrote. “After the sham-interview incident, however, Glicksman recommended tenure ‘without enthusiasm,’ thereby setting in motion Shoucair’s tenure denial.

“One could infer that Glicksman knew that the effect of placing those words on Shoucair’s report would result in a denial of tenure.”

In court papers, Brown contended that the evidence showed Gilcksman didn’t know about Shoucair’s objections. He allegedly voiced his concerns to Glicksman’s secretary, Sandy Spinacci, although she denied it.

“While Glicksman’s secretary, Spinacci, was clearly a good soldier who was in an extremely awkward position, her testimony and that of Glicksman was not compelling or persuasive in the least,” Gibney wrote.

After leaving Brown, Shoucair taught for a few years at the University of California at Berkeley, where he lives.

But he’s not working now.

“He’s tending his gardens,” Siegel says. “He’s in limbo. He would like to be working in his field.”