Critic of campus’ ties with biotech lost initial bid

Critic of campus’ ties with biotech lost initial bid

A widely watched tenure battle at UC Berkeley has ended in victory for assistant professor Ignacio Chapela, an outspoken critic of campus ties to the biotech industry.

The university has reversed its 2003 rejection of Chapela’s tenure bid and hired him as a regular member of the faculty, campus spokeswoman Marie Felde said Friday.

Chancellor Robert Birgeneau rendered his decision on hiring Chapela early this week, Felde said. Birgeneau agreed with the recommendation issued in late April by a six-member faculty committee appointed to review Chapela’s case after he appealed the tenure denial, Felde said.

His new position as an associate professor is retroactive with back pay to 2003, the year former Chancellor Robert Berdahl denied the tenure bid, Felde said. A different faculty committee then had recommended against hiring Chapela, who teaches microbial biology.

“I was quite surprised,” Chapela said of the reversal. “I think there’s some recognition that vindicates the legitimacy of my position.”

“It’s wonderful news,” said Chapela’s attorney, Dan Siegel. Chapela sued the campus April 18, alleging he was “a victim of retaliation.” Siegel said no decision has been made on whether to proceed with the suit.

Chapela’s supporters linked the rejection to his role as a leading opponent of a five-year deal struck in 1998 that gave biotech giant Novartis privileged access to UC plant research in exchange for $25 million.

His tenure application began with unusually strong support from his peers. Faculty colleagues in the environmental science, policy and management department voted 32-to-1 in favor, and a five-member ad hoc tenure committee gave unanimous approval to hiring him.

But his bid was rejected by a third faculty committee that included a member who also served on the advisory committee for the Novartis deal — a fact that helped inflame widespread controversy over the case.

A review of the UC-Novartis pact completed last year by Michigan State University researchers concluded that there was “little doubt” that the deadl played a role in the denial of tenure to Chapela.

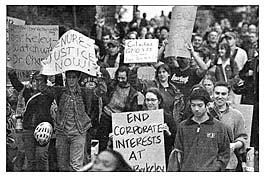

His cause was bolstered by many supporters, about 100 of whom marched to Birgeneau’s office in December to present a petition on his behalf signed by 320 people, including 145 university professors from across the United States and several other nations.

The Chapela case drew prominent coverage in the Chronicle of Higher Education and the science journal Nature. The Novartis compact featured prominently in an Atlantic magazine cover story, “The Kept University,” in March 2000.

Chapela made news also because of a disputed article that he and former graduate student David Quist published in Nature, alleging that genetically engineered corn had infiltrated native maize in Mexico. Nature later issued an apparent retraction, saying “that the evidence available is not sufficient to justify the publication of the original paper.”

Chapela and supporters planned to gather Friday night for a celebration and rally at the construction site for rebuilding Stanley Hall, slated to become Cal’s bioengineering and biosciences center.

They staged rallies and bike rides around Stanley this past week with banners challenging Berkeley research and publicizing their Web site at www.pulseofscience.org.

“Needless to way, we’re extremely excited,” said Jesse Reynolds, a former student of Chapela’s who helped organize the tenure campaign.

Birgeneau is unlikely to comment, Felde said. “He respects that while this has been a high-profile case, it does remain a confidential personnel process.”

Attorney Siegel called the victory “a testament to Professor Chapela and his outstanding academic record and to the tremendous support he received from faculty members and students, not only on the Berkeley campus, but throughout the world.”